It was a sunny spring afternoon. I went to an art criticism seminar and heard that the burial sites created three years ago due to foot-and-mouth disease and avian influenza had become legally usable land. It wasn't specifically directed at me, but for some reason, those words stuck clearly in my ea...

It was a sunny spring afternoon. I went to an art criticism seminar and heard that the burial sites created three years ago due to foot-and-mouth disease and avian influenza had become legally usable land. It wasn't specifically directed at me, but for some reason, those words stuck clearly in my ears.

It was the winter of 2010. News was reported daily about animals being buried alive. Trucks loaded with pigs dumped them into pits. The pigs struggled in the air and screamed. Thousands of ducks waddled and were chased into pits, rolling down with a thud. Dirt was poured over animals that looked around in confusion, not understanding what was happening. Only then did I understand the meaning of the word 'culling.' The word 'shock' was not enough. 'Is it okay to treat living beings like that?' Something deep inside me was damaged by this cruel and brutal reality.

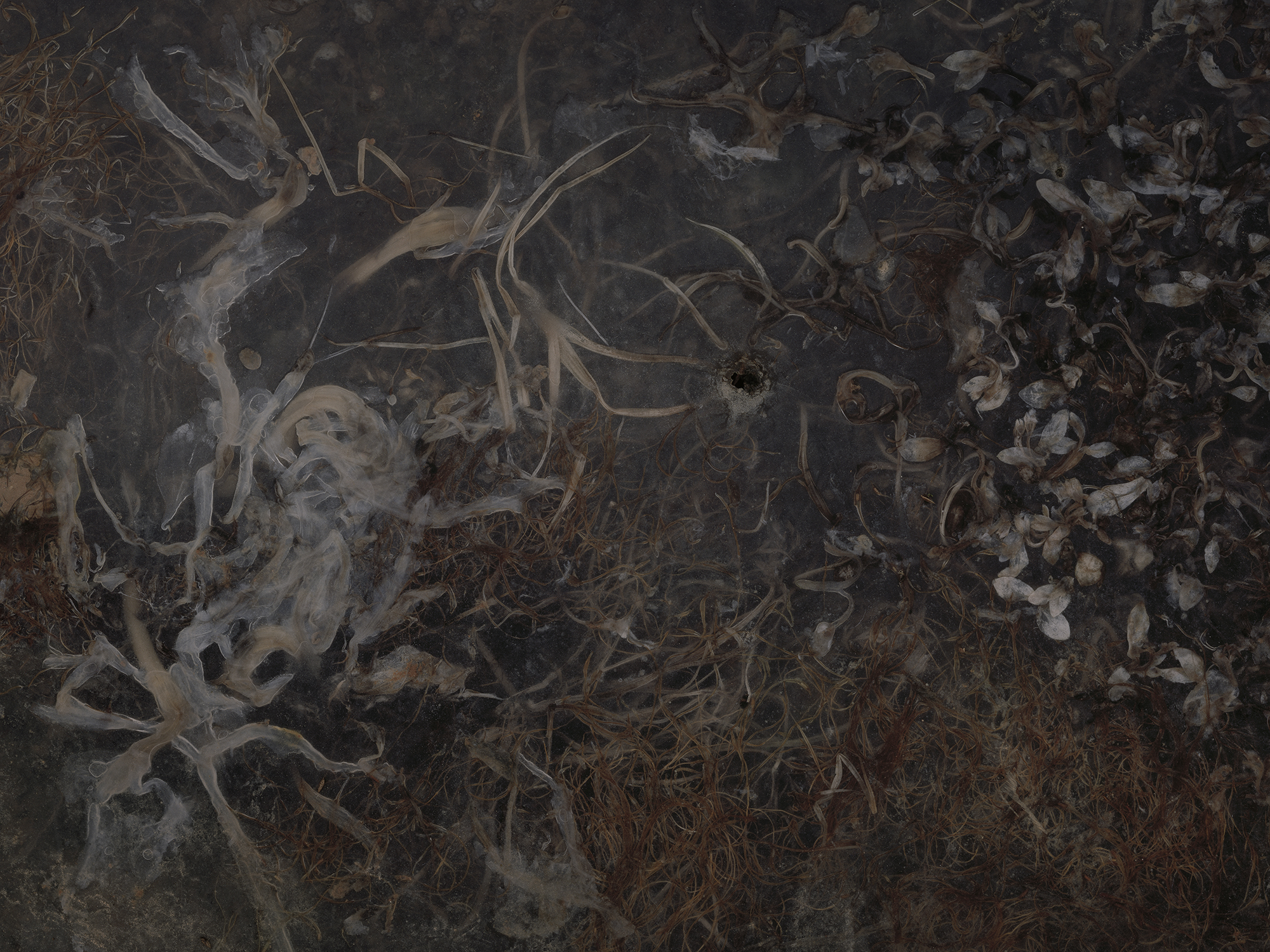

The burials proceeded urgently. Countless lives were buried alive. The government solemnly declared it was the best solution. Many people were mobilized. The work of pushing living beings into pits scarred their innermost depths. Blood seeped from the land that had swallowed life. Half-rotted corpses shot up into the air.

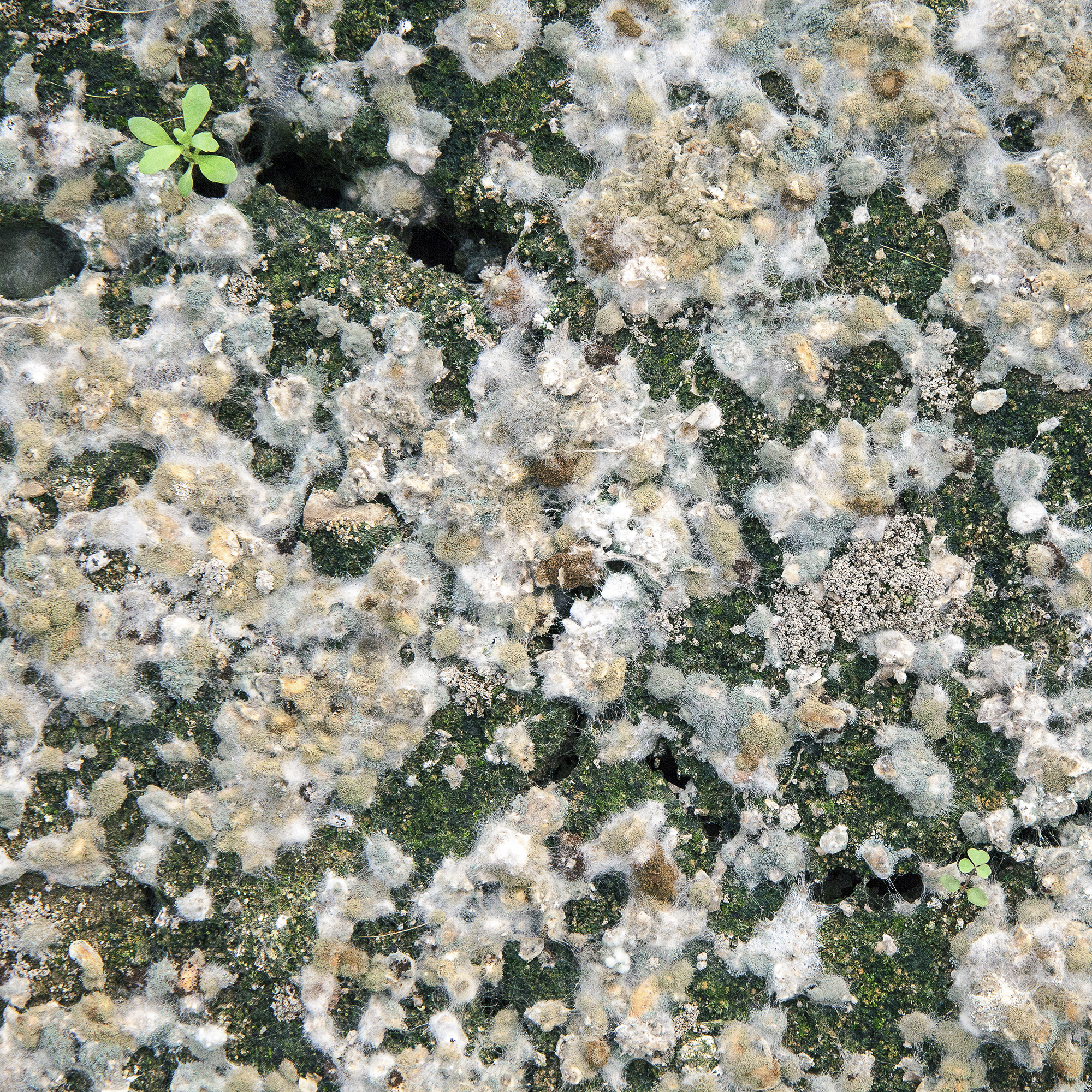

In 2014, without much news, the legal excavation ban period was lifted. The 4,799 places of ominous land that had swallowed over 10 million lives three years ago became usable land. Did it really become usable land? With a worried heart, I went to a burial site relatively close to home. It was a vinyl greenhouse. The inside was empty. I went inside to look around. The ground squelched and wobbled. I was startled and stepped back. Everywhere I stepped, it squelched and distorted randomly. It was completely different from stepping on snow or mud. The hair on my head stood on end. To make matters worse, mold like cotton balls sprouted from the cracked ground. What was happening down there?

I examined about 100 of the burial sites where the legal excavation ban had been lifted. Most burial sites were left abandoned, covered with vinyl. The stench of rotting corpses rose from various places. The earth's movements were unusual. The land, shadowed by death, had turned black. It sometimes spewed mold through cracked gaps. Grass that had barely sprouted died strangely while vomiting liquid. Diligent farmers tried farming. Beans wouldn't grow, and chives grew slowly. The rice fields were thick with insects, and corn and sesame rotted and fell. These were scenes we had never experienced before.

Infectious diseases repeat every year. The government makes rules and buries without exception according to those rules. There is no death there. Only products are discarded. While judgment is castrated and only efficiency operates, animals lose the opportunity to develop immunity, and the land loses its self-purification ability.

I lowered my body and listened to the earth's voice. Animals that had not yet returned to soil shook me with their squelching touch. The land rotting whole, the strangely dying grass, and the vinyl used for killing remained without rotting, silently testifying to what we had done.

This work is a record of the land where, along with animals buried alive by our social system that operates based on rationality and economic efficiency, our humanity was also buried.